My journey into personality studies began 10 years ago when I had the unfortunate luck of having a sociopath as my manager. I’ll avoid the gory details other than to say that the experience was transformative, and left me with a very different perspective on the nature of evil than I’d had before. I ceased believing that all people start out inherently good (or even inherently neutral) or that malicious traits only arise due to traumatic experiences.

Since that time I’ve explored personality, and the conceptualization of dark personalities, across many fields, including psychology, social and political science, behavioral economics, cognitive neuroscience, cultural anthropology, and game theory. After years of researching how dark personalities evolved, what behaviors they exhibit, which environments they thrive in, and how various cultures have dealt with them, I’ve come to a somewhat startling conclusion. I believe the common thread tying together every component of the polycrisis humans face today — from environmental collapse, to political instability, to wealth inequality — is the success of sociopaths and their values in the absence of adequate social controls.

Sociopaths have always existed, but ethnographic data and historical evidence both indicate that early human groups had effective ways of dealing with them. Such groups were small enough for everyone to know each other personally, so it was easy to tell who was selfish or deceitful, who avoided work, who cheated, and who routinely took advantage of others. Early socialization and positive pressure by adults encouraged pro-social behaviors among group members, and cultural norms and rules promoted an ethos of sharing and egalitarianism. When these norms were violated, this fact would generally be shared through gossip, undermining the offender’s reputation. If that didn’t quell their behavior, group members might collectively discuss the problem and impose sanctions. And if an offense was serious enough or repeated too many times, capital punishment was an accepted way to protect group members from continued exploitation and abuse by such individuals.

Over time conditions emerged that began to undermine the strategies that had successfully contained sociopaths in hunter-gatherer groups. Some groups began cultivating crops, abandoning nomadic lifestyles to live in more permanent settlements. When these crops produced a surplus above what was needed for consumption by the group, settlements could become larger and support job specialization beyond agriculture. Larger settlements posed new problems, however. Beyond a certain number, it’s impossible to know everyone around you well enough to determine whether they are trustworthy or exploitative. The larger a settlement becomes, the easier it is for dark personalities to conceal their true nature from those around them or move to a new group to avoid the effects of a bad reputation once they’re discovered.

In addition to allowing permanent settlements, agricultural surpluses facilitated the accumulation of wealth and property. Although many cultures have managed surplus cooperatively, its existence can just as easily provide a toehold for greedy sociopaths (greed is a key trait of dark personalities) to start hoarding wealth, especially when egalitarian norms have eroded or failed to adapt to changing social and material conditions. Though power doesn’t automatically flow from wealth, the two can become linked when individuals are allowed to use their wealth to purchase the loyalty of others.

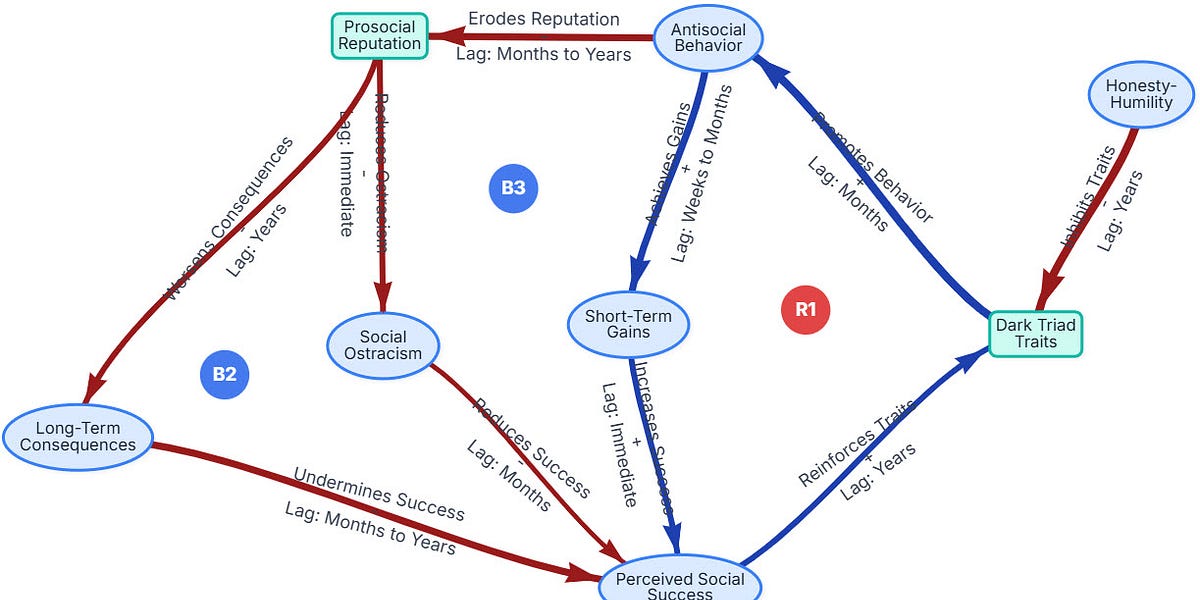

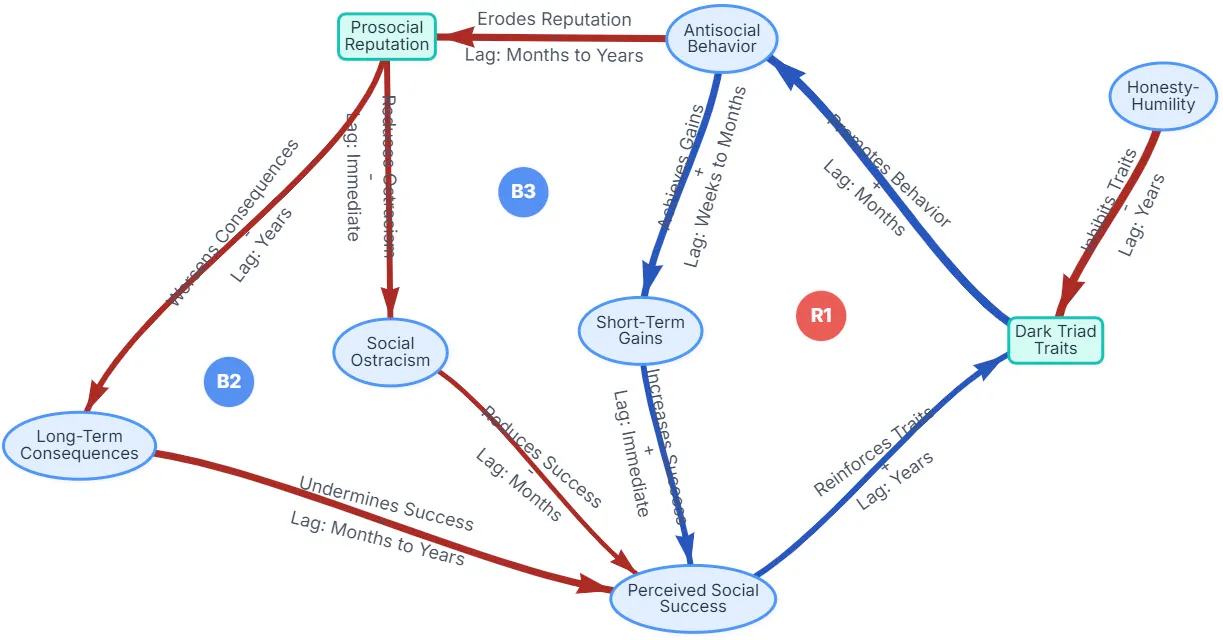

Without feedback mechanisms in place to maintain egalitarian norms, wealth and inequality tend to grow via self-reinforcing loops. With proxies available to do their bidding, it becomes much easier for bad actors to extend their reach and gain control of additional resources. An inflection point occurs when sociopaths accumulate enough power to begin influencing culture, norms, and social systems in ways that legitimize their privilege and propagate their selfish, exploitative values. In effect, they gain the ability to shape their environment to facilitate their wealth and power hoarding at the expense of the group, while simultaneously suppressing mechanisms that might keep them in check. This process bears an uncanny similarity to the behavior of cancer in the human body: prioritizing the self over the whole, consuming outsize resources, and metastasizing.

Once sociopathic values permeate and reshape cultures, they become camouflaged in legitimacy. Without exposure to alternative approaches, we tend to accept the systems we’ve grown up with as the inevitable culmination of human progress. But if we look hard enough, we notice that sociopathic traits — greed, craving power and status, entitlement, dishonesty, and manipulativeness — are baked into our institutions. Our economy is predicated on endless growth and extraction in a world with finite resources and carrying capacity. Our political system allocates power and influence on the basis of hoarded wealth rather than collective interests, wisdom, or experience. Our foreign policy condones genocide if it supports our strategic interests. Our media glorifies and rewards shallow narcissism over substance or deep engagement. The examples are endless, but it’s important to realize that these are all choices and not predetermined outcomes.

If we want to avoid the most dire consequences of the polycrisis, humans must understand sociopaths and the causal role they have played in unleashing these threats. For instance, an examination of how dark personalities exercise power reveals potential leverage points that might be used against them. Only a small number of sociopaths have the combination of traits necessary to project influence on a massive scale, and this is only possible if they can amplify their will via wealth, power structures, and media conduits. Cutting sociopaths off from these amplifiers could be an effective way to short-circuit their ability to manipulate others and propagate their values.

Socialroots friend and prolific causal mapper, Gene Bellinger, explores the dynamics further in this post:

To have any hope of creating a new, sustainable society that isn’t controlled by the worst among us, we must leverage our understanding of dark personalities to develop robust governance structures, economic systems, and cultural norms capable of containing them and their exploitative tendencies. If we can contain the sociopaths, we just might save the world.

Socialroots is building technology with the creation of a social immune system in mind. Here's more from us on cooperation in and across groups.

=> If you enjoy this research, you can also support our cooperative here.