Balancing trust and security while enabling large-scale coordination

Authors: Ana Jamborcic, Ann Stapleton, Szilard Hajba, Sergey Shadar, Kenneth Bruskiewicz

‘Who Gets Edit Rights?’

We thought we were solving an easy tech problem. Three organizations wanted to share a document folder. Pretty basic stuff.

Then someone asked: "So who gets edit rights?"

The room went quiet.

None of the three groups owned the folder by themselves. Each group had its own structure—leaders, regular members, and supporters. Should leaders automatically get editing power? What happens when groups disagree about permissions? Who decides?

What seemed like a simple question about access had opened something much bigger: How do you build systems that are open enough to let everyone participate, but organized enough to actually get things done? (As Jo Freeman observed in her classic essay "The Tyranny of Structurelessness", pretending there's no structure doesn't eliminate power dynamics—it just hides them.)

The Problem With Technical Solutions to Social Problems

Someone suggested a quick fix: create two basic rules. First, everyone gets at least some access to information. Second, there's a limit on sharing sensitive stuff. Between those rules, people decide for themselves what to share.

It sounded smart. It sounded complete. It also sounded like a nightmare to manage.

Then someone shared a game-changing observation: "I've seen people put Google Docs on completely public settings, fully editable, and have zero problems for years."

The silence that followed was different this time. Not confused—understanding.

The real key wasn't fancy encryption or complicated access controls. It was about who had the link. We were building complex technical security to fix something else entirely: the lack of good ways to figure out who to trust.

Most decentralized protocols—Nostr, Bluesky (ATProtocol)—are fundamentally trustless. A bot from Russia has the same permissions as your closest collaborator. This is treated as a feature. But for cross-organizational coordination, it creates exactly the wrong setup.

Here's the radical question: What if the architecture itself is wrong? What if we need a collective identity built into the protocol from the start, not access controls awkwardly added on top of systems designed for individuals?

Think about it: we're trying to retrofit group permissions onto systems that were designed assuming everyone is a stranger. We're adding layers of complexity to compensate for a fundamental design choice. What if communities don't need more security features? What if they need better "membranes"—better ways of deciding who's trusted and how much—and then the technical stuff would get way simpler? (Elinor Ostrom's research in Governing the Commons shows how communities naturally develop these trust boundaries.)

The Developer Mindset vs. The Community Reality

Here's where it gets interesting. Software developers usually start with maximum security and slowly add openness. But communities doing real collaborative work? They often start wide open—like social media—and only add security when something goes wrong.

In real life, generous sharing usually works better than strict rules. Heavy permission systems slow down teamwork more than the occasional trust problem costs you. When you're already working across different groups, you're not trying to keep everything private anyway. (Nadia Eghbal explores these collaboration patterns beautifully in Working in Public.)

But this can't work everywhere. Companies, lawyers, and hospitals need real security. The question becomes: how do you design systems that don't force everyone to use the most paranoid settings?

Fork This

Here's the uncomfortable reality about decentralized systems: splitting off is always possible. Anyone who gets information can do whatever they want with it on their own computer. You literally cannot stop this. The question isn't "can they edit?" but "will the original group accept their changes?"

This creates a basic truth. Decentralized systems must accept that people can always create their own version. You can fork Bitcoin. You can fork a community's shared documents. The system can't computationally prevent this. (Eric S. Raymond's The Cathedral and the Bazaar explores when forking strengthens rather than fragments communities.)

But if everyone can split off, you risk chaos—thousands of versions with no agreement on which one is "real." How do you give people freedom while keeping enough organization to work together? How do you prevent three million untrackable copies?

The Breakthrough: Three Layers Working Together

Someone described the circulatory system and it clicked: your body has three layers working together. Central organs broadcast hormones into the bloodstream (top layer). The circulatory system carries these messages everywhere (middle layer). Individual cells receive the signals but decide locally whether to respond based on their immediate conditions (bottom layer). No cell asks permission from your brain to process glucose—but they all stay coordinated through shared signals.

Pure top-down control becomes rigid—secure and stable but slow and bureaucratic. Pure freedom fragments into chaos.

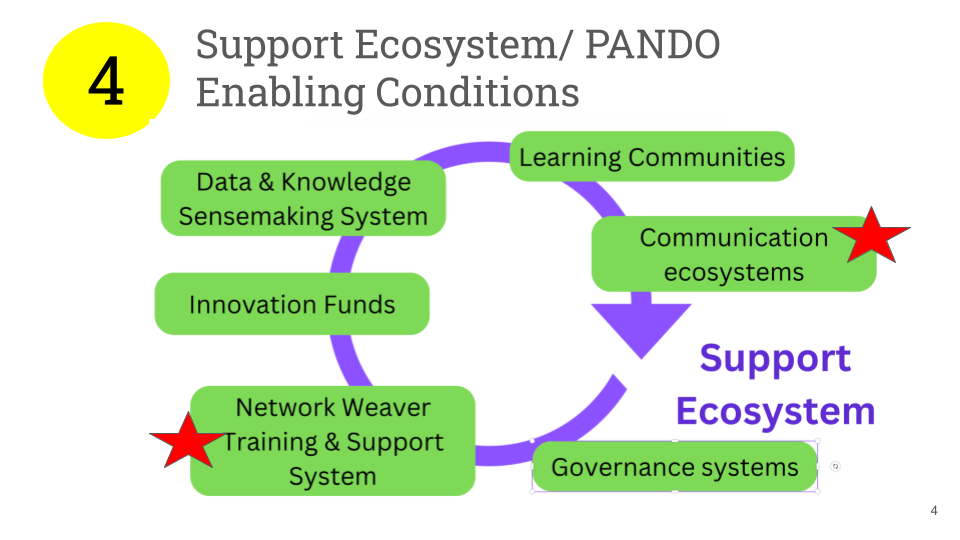

What you actually need is three layers working together. Think federal, state, local government—or company, team, project. The top layer provides stability and big-picture direction. The bottom layer provides flexibility and testing new ideas. The middle layer lets information flow between them.

Each layer does something different. The trick is designing systems that support this natural structure without creating a crushing hierarchy. The layers need to connect without the top level destroying local freedom. (Donella Meadows' Thinking in Systems offers an accessible introduction to these multilayered dynamics.)

Don’t Have A Computer Do A Person-Job

A crucial insight emerged late in our discussion: we shouldn't try to "compute away disagreement."

When different people have conflicting ideas about permissions, the system's job isn't to solve this with an algorithm. It's to make the conflict visible so humans can talk it out.

This suggests a completely different approach to permission systems. Instead of preventing all possible conflicts with complex rules, design systems that spot conflicts and flag them for human attention. Create "good enough" default settings that handle most situations while staying flexible for the rest.

The goal isn't to eliminate tension. It's to make tension useful.

We Don't Have All the Answers, Just Better Questions

Decentralized systems work like tension structures: opposing forces creating stable shapes through balanced pressure. You need the pull of independence and the push of coordination. You need openness and boundaries. You need the freedom to split off and the gravity to work together.

The open questions that still matter:

- How do we build trust-based permission systems in decentralized networks?

- What are actually good default strategies for different situations?

- How do we design systems that relax their rules when security overhead becomes more trouble than it's worth?

- What makes some splits productive versus destructive?

These questions sit at the crossroads of technology, social behavior, governance, and politics. They're the questions that come up when you try to build systems that spread power around instead of concentrating it.

If you're working on decentralized systems, you're dealing with some version of these tensions.

Further Reading

Want to dive deeper? Here are some resources organized by topic:

Decentralized Governance & Collaboration

- Working in Public by Nadia Eghbal - How open source communities actually organize and collaborate

- Patterns for Decentralised Organising by Richard D. Bartlett - Free handbook with practical patterns for decentralized teams

- Moving Beyond Coin Voting Governance by Vitalik Buterin - Exploring governance challenges in blockchain systems

Trust, Boundaries, and Community

- The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman - Why "no rules" doesn't mean "no power dynamics"

- Governing the Commons by Elinor Ostrom - How communities self-organize and manage shared resources

- 1,000 True Fans by Kevin Kelly - Building trusted networks and meaningful community boundaries

Forking, Branching, and Divergence

- The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric S. Raymond - Classic on open source development and productive forking

- Exit, Voice, and Loyalty by Albert Hirschman - Economic theory explaining why the ability to "exit" (fork) matters

Systems Thinking and Layered Organization

- Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows - Accessible introduction to systems thinking

- Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal - Case study on layered autonomy from military operations

- Polycentric Governance by Elinor Ostrom - Research on multi-layered governance systems